As workmen dig up Farnham town centre’s roads in the coming weeks, they may well uncover relics of its past - thanks, in part, to a certain Oliver Cromwell.

Although there is no record of large-scale battles taking place on the streets of Farnham, the English Civil War had a significant impact on the town and its people.

At the time, England was divided between supporters of King Charles I (Royalists) and those loyal to Parliament (Parliamentarians, or Roundheads).

The townspeople of Farnham were, on the whole, Royalists.

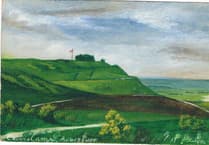

However, the Parliamentarians saw the strategic importance of Farnham Castle, which sat on the key route between London and the south coast, controlling access to Winchester, Southampton, and other vital towns.

Early in the war, Sir William Waller, a leading Parliamentarian commander, seized Farnham Castle and transformed it into his headquarters for operations across southern England.

The castle was of great tactical importance, and Waller used it to control the surrounding countryside.

His forces garrisoned the stronghold and set up encampments in Farnham Park, where soldiers lived under strict military discipline.

A gallows was erected there, where those found guilty of mutiny were hanged as an example to others.

According to local legend, a second gallows stood at the bottom of Castle Street, along with stocks used to punish minor offenders.

It is also believed that a signalling post was positioned in West Street, allowing military detachments to communicate between the castle and the town.

Despite being occupied by Parliamentarian forces, Farnham remained vulnerable to Royalist counterattacks.

In 1643, Royalist commander Sir Ralph Hopton led an army into Hampshire, hoping to challenge Parliamentarian control in the region.

But after a series of engagements, including the Battle of Alton and the storming of Arundel Castle, Hopton’s forces were gradually pushed back.

Parliamentarian cavalry pursued the retreating Royalists, capturing prisoners along the way.

Among them was Bartholomew Ellicot, who had recently switched allegiance from Parliament to the King.

He was hanged in the marketplace at Farnham at the aforementioned Castle Street gallows as a warning to others.

Rather than one continuous conflict, the English Civil War was a series of smaller civil wars from 1642 to 1651, and following the Second Civil War in 1648, Parliament took steps to prevent Royalist sympathisers from using Farnham Castle in any future uprisings.

That year, the castle was ordered to be “made indefensible,” meaning its defences were deliberately damaged to render it useless for military purposes.

Oliver Cromwell himself visited Farnham Castle, and during this period, much of the keep was dismantled - leaving the gaping hole in its eastern wall we see today.

The destruction of the castle led to an unexpected benefit for the townspeople, however. With large amounts of rubble left behind, local residents used the stone to surface roads.

Even today, when roadworks go deeper than a metre beneath the surface in certain parts of the town, remnants of the castle’s limestone can still be uncovered.

In 1649, King Charles I was tried, convicted of treason, and executed - staying at Farnham’s Vernon House (the modern day library building) on his last night of freedom.

The monarchy was abolished, and for the next 11 years, England was ruled as a republic under Cromwell’s leadership.

During this time, Farnham remained a Parliamentarian stronghold, garrisoned by troops until the end of the First Civil War in 1646.

In 1660, following Cromwell’s death, the monarchy was restored, and Charles II ascended the throne. One of the first priorities was to repair the damage done during the war.

Bishop George Morley, an influential supporter of the monarchy, oversaw the restoration of Farnham Castle. He invested heavily in repairs and renovations, ensuring that the castle regained its former grandeur.

Morley was responsible for many of the improvements to the Great Hall, and his additions included a magnificent minstrels’ gallery and a vast stone fireplace, symbols of the return to stability after years of conflict.

.png?width=752&height=500&crop=752:500)